Everything Everywhere All at Once: Spectacular and Flat

Graphic unfortunately by Seoyoung Joo

The biggest immigrant story of this past quarter is probably Everything Everywhere All at Once.

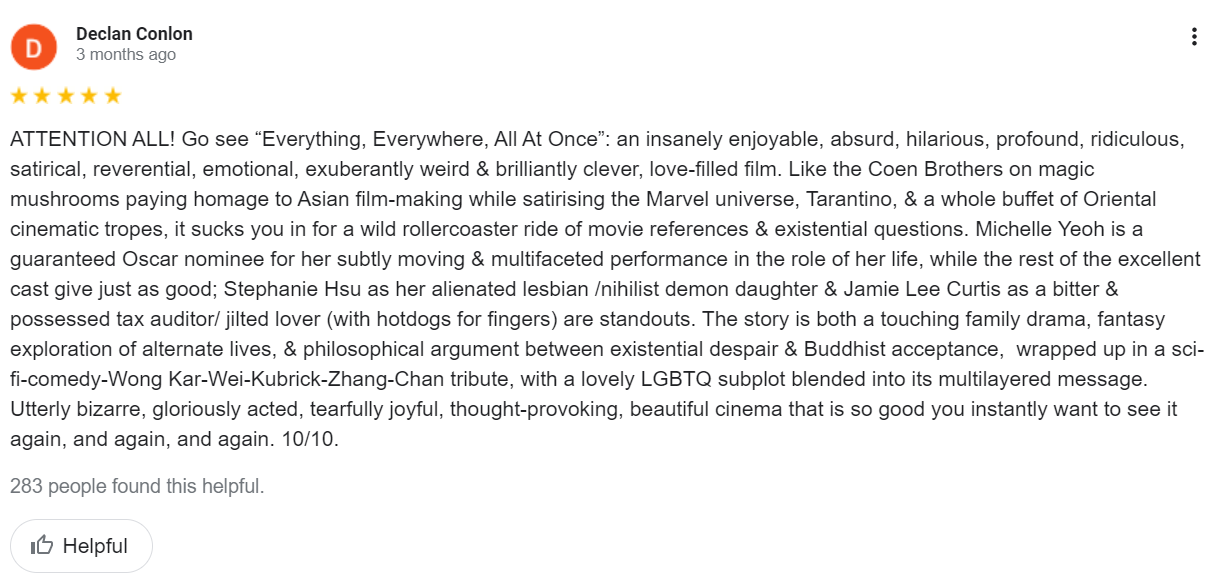

One of my favorite exercises to do with a movie once I’ve watched it, before I’ve really started to put together an opinion, is to pull up the Google reviews. What I love about Google reviews is that there are many words being written. These words create a space to drag out the subconscious and outline yet unformed thoughts and emotions so I can better grasp exactly how I feel. What’s perfect about Google reviews is that the amateur lens asks you to specify their sweep over the movie production and storyline, the review’s writing being more involved in pouring praise on actors and tropes rather than specific story beats. Why does that actor work in that position? Rather, what was the point of the story being told, and how does that actor’s performance enhance or detract from it? Google reviewers tend to have a good grasp on “what is supposed to be,” and that helps clarify my own thoughts.

Let’s pull up the movie reviews of EEAAO.

Much like the other Asian immigrants or children of Asian immigrants who watched this movie, I did cry throughout its runtime. The oft-retweeted Twitter post about EEAAO features a friend group, comprised of children of Asian immigrant parents, holding themselves in different poses of exhaustion and release, on the ground and against the wall. Leaving the theater, I felt like I had been moved. By the time I had gotten on the bus, I started feeling like someone who had impulse-bought a bus pass for three days, figuring that it would be cheaper in a bundle, only to realize the price of the three-day bus pass was exactly equivalent to three one-day bus passes. And that I wouldn’t be able to ride the bus tomorrow because I was going out of state. There were many words, but my point is that despite my original positivity, I wasted my money watching this movie.

The focus on the mother as a person and character is interesting—the Asian immigrant stories I’ve seen in English are usually focused on the intergenerational trauma that the American daughter feels, and how the values she’s taught at school and through her circle of American friends clash with what her parents expect or want from her. I liked that there was a more sympathetic idea of the mother, Evelyn. She’s too busy to have the emotional space to explore who she wants to be. We get to explore her dreams, her connections, and her regrets in regard to her family. How her struggle to stay financially stable as an American immigrant sidelines these thoughts. I thought of my own mom watching her, remembering how much she couldn’t be at rest because of her full-time job.

But past that, there’s very little to define Evelyn. For a story about her, we know very little about her; how she grew up (a flash—a portrait of a tense family), what her parents were like (implied to be difficult, but not much beyond that). We don’t even know what region of China she’s from. We know even less about her husband, Waymond, other than the idea that he’s a “loving spouse,” and Evelyn’s foil as an emotionally “good” parent, having the space to chase after his emotional needs through a divorce statement. Joy, the daughter, is a disaffected, troubled adult who is struggling to find her way in life, outside and inside of the family. It’s a very unspecific movie. To sum it up, EEAAO is about a Chinese-American family, where the mom has cultural differences come between her relationship and her daughter. But that’s as vague as you can get. This could apply to any “immigrant story” about an “Asian-American family” that “struggles with cultural differences.” Really, we can broaden this to be about the “intergenerational gap,” which at the very least is not limited by the constraints of the tropes seen in an “immigrant story.”

The interviews with the directors, the Daniels, clarify parts of the personalities of the characters. Evelyn is described to be “imagined” as if she had “undiagnosed ADHD” in an NPR interview. Joy is described as being depressed. It is a shallow drive. Evelyn could have ADHD. But instead of going into how this might have affected her life and her experiences, and how that then leads into her marriage with Waymond and her relationship with Joy, it’s just used as a fun trivia fact to look for. Same with Joy. We don’t actually get much from her other than that she’s “depressive.” What are her motivations? Does she not have any? What does she want to do with her life? We don’t know, because EEAAO does not care. She is simply a Disney plus sitcom teenager, misunderstood and rebellious.

EEAAO is not concerned with figuring out who these people are or why exactly they might do the things they do. They are attracted instead to the tropes (the “tiger mom”) antagonizing the immigrant parents. When Evelyn tells Joy she’s “fat” and “needs to watch what she’s eating,” Joy does explain to the audience that she says these things out of love. But it’s too fast and too “one-liner,” trying to sum up a complex mother and daughter idea via an Easter egg-esque moment. And then the movie frowns on Evelyn, showing Joy crying as she runs to the car when Evelyn repeats that sentiment to her “out of love.” Yes, there are misunderstandings between American and Chinese culture. But it’s spelled out for the viewer by condemning Evelyn’s actions towards Joy, even as she tries to protect her; when she lies to her father about Joy being a lesbian, it could have been portrayed in a gracious way, knowing that to Evelyn, her own interactions with her father (which she has years of practice and trauma with according to the movie) spell danger for her only daughter. Of course she would lie! But the movie sides with Joy, not Evelyn, despite the movie being focused on Evelyn as the star. Joy is the stand-in for the white American gaze, striking out at injustices she (white American culture) perceives from Michelle Yeoh (what is asserted to be “Chinese parenting”).

This being labeled as an “Asian-American” story is apt. EEAAO flags itself as “authentically Chinese” with scenes from Hong Kong, the characters speaking in Chinese, and Michelle Yeo being a wuxia star. As a symptom of the lack of care in character development, there is very little exploration into the culture itself. What’s notable about a lot of the reviews I’ve seen surrounding this movie is that despite the implicit understanding of the “cultural value” EEAAO has, there is very little discussion of the cultural portrayals themselves. From the first review, one out of two mentions is here:

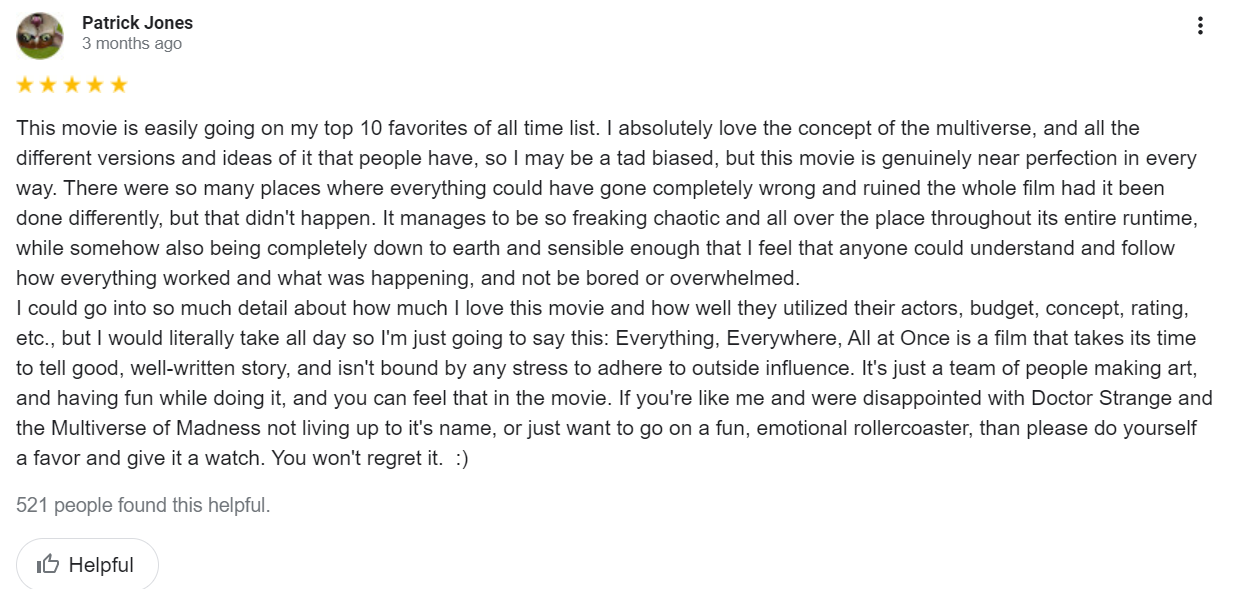

The second review doesn’t mention “culture” at all. That’s the magic of this movie—by having a thin veneer of “Asian-ness” over a “down-to-earth and sensible” story, it’s easily digestible and not too challenging to the everyday moviegoer.

One of the ways EEAAO adapts a potentially complex story into relatability is by making an appeal to the “Asian-Americans” and the “Asian-American experience.” This is instantly flawed because cultures that fall within the “Asian-American'' sphere are very, very different. It’s easy to forget—sometimes I even catch myself assuming that I would know things about Chinese culture because Chinese and Korean culture are conflated so often in the use of chopsticks, ancestor worship, and specialty supermarket brands. But even just within Japan, Korea, and China, each country has very different cultures towards speaking, honorifics, what the work sphere looks like, what jobs are valued, what home life looks like, who stays at home, who is taught at school, and how this translates to the US. And this is just part of the East-Asian sphere, which is the stereotypical content of the “Asian-American,” especially in EEAAO. But if we expand the Asian-American sphere to truly include all of Asia, EEAAO conflates the East-Asian cultures with the wide diversity of experiences, homes, and regions in India, Thailand, Pakistan, and Iran. And to conflate is to write over, or to exclude entirely from the story, because some cultures don’t fit into the idea of “Asian-American.”

Even EEAAO asserts this “Asian-American” generalization—not purposefully, but by overgeneralizing the family’s story. The parents are from China (not discussed or specified, but simply implied from the flashes backward and forward). The mother is not a mother, but simply Michelle Yeo, a “tiger mom” who just wants the best for her daughter and does that by antagonizing her. The daughter, to borrow my roommate’s words, is some mysteriously disaffected adult struggling to find a path in the world as well as communicate with her family. What exactly is she struggling with? Finding a job? Looking for something she’s interested in? Talking to her family about setting boundaries and finding love within those boundaries?

Food, we are told, is the immigrant way of showing love. Sure, but most families, historically American or first generation, have noted the food = love statement. The reality is that it acts as a flag to tell the audience we are “real” Asians making an “authentic” foreign movie. We are stepping out of the “American,” the images say. Put on your seat belts. But by using culture as signals, not giving them the space to breathe as their own themes and functions, the cultural words lose meaning and depth in the context of the story. It trivializes “Asian culture” as backdrops to a “foreign story,” one that has to be simplified, not explored, for non-immigrant audiences. Even though a story told well will be moving enough for watchers to understand, even if they haven’t lived through that specific experience. It cheapens immigrant stories as a gimmick, not an experience. A skin over the white American story told about Asian immigrants. The first review actually hits this idea spot on with word choice:

& a whole buffet of Oriental cinematic tropes

It’s a Disney movie, and that’s how EEAAO fails. It’s Encanto, where years of worry and habit are “fixed” by getting the family back together. I wished that Encanto had been a TV show, with more character studies, more sister bonding, and learning new things about the relatives you believed had to be close to you. That might have been too much to ask for a children’s movie, where it has to tell a story compactly and in a way that kids will understand. EEAAO challenges the watchers to follow the spectacle and find the story under it, but the story is shallow and flat. All of the work went into the sci-fi, not the movie. You can’t have a good immigrant story by simply changing the genre—you still have a sci-fi immigrant story, not a story. It’s flashy, it’s boring, and it does the “Asian-American” story a disservice.

We need more real stories. Stories about who the parents are, what they do, how they aren’t just “bad” tiger moms but real mothers. Women with worries, trauma, and logical reasons for the actions they undertake, especially when they’ve been pushed and pulled by the incredibly difficult action of immigration and adaptation into a new country. As long as we keep demonizing the most “Asian” people in our families, the story will strain against reality to accommodate our “Asian-American” line. To be authentic, we must be real and challenge the tropes and narrative conveniences of the “immigrant story” with specificity, sympathy, and the unique Asian-American worldview.