Anime, Aesthetics, and the Asian Diaspora

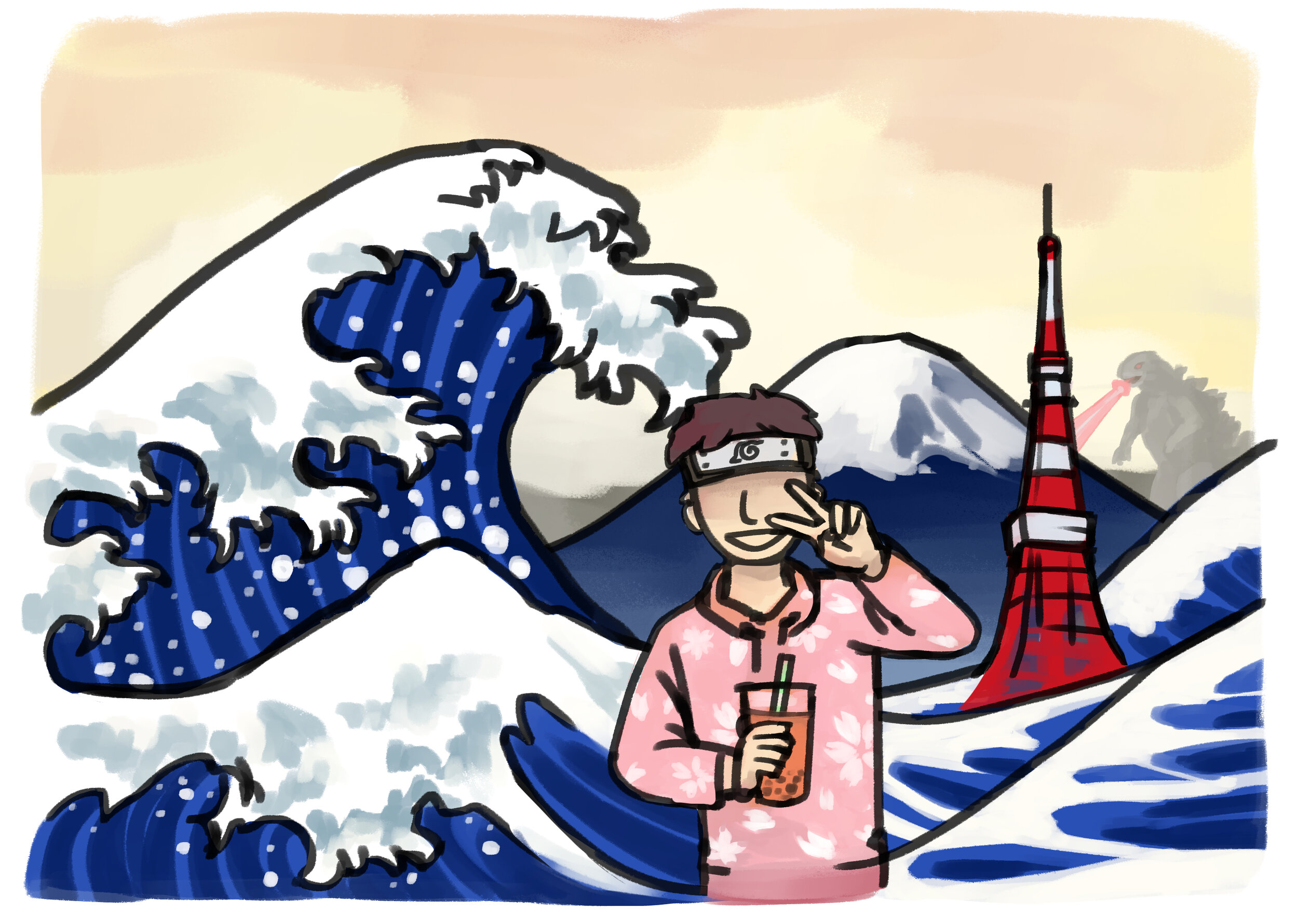

Far too often, Americans judge culture by their most popular exports. They remain armchair consumers of foreign media, consuming what comes to them rather than actively seeking it out. In 1954, when Godzilla first hit American theaters, Americans were astounded and confused by the views of a large monster destroying Tokyo. They may have been impressed by the horror and special effects at the time, but without context, they could never fully comprehend what they were seeing. Nine years before, Japan fell victim to the only two nuclear attacks in the history of the world. Japanese people were acutely aware of the destruction that nuclear weapons could wreak, and Godzilla, in some respects, was a projection of their anxiety.

Now, a new genre of Japanese media has established itself as a cultural juggernaut. Japanese anime has been steadily growing in popularity since its arrival in the United States thirty years ago. If you were my age, and grew up in an Asian-American household, it’s likely that you also watched early anime like Pokemon or Dragon Ball. The anime-related posts on the Subtle Asian Traits Facebook page are almost as numerous as the boba-related posts. However, I would caution members of the Asian diaspora from shaping their identity around products meant for consumption, like anime and boba.

“The commodification of difference...threatens to flatten and cannibalize the difference while stripping it of all historical context and political meaning”

Jenny G. Zhang’s “The Rise and Stall of the Boba Generation” covers the history of bubble tea, the ways in which it represents the diversity of the Asian diaspora and ultimately, how it demonstrates the limits of a shared “Asian” identity. In many respects, what we in the West consider “Asian” is a patchwork of cultural commodities assembled from mostly East Asia. So, we get boba from Taiwan, pho from Vietnam, kpop from Korea, and anime from Japan. The danger that Zhang, and scholars of the Asian diaspora present is that western Asians will consider their identity to be purely based upon the consumption of products, without cultural context. “The commodification of difference...threatens to flatten and cannibalize the difference while stripping it of all historical context and political meaning”.

Unlike boba, which is consumed by taste, Japanese animation, or anime, is a visual medium. Anime is one of the most popular cultural exports from Japan, both within and outside the Asian diaspora. It has art traditions rooted in ancient Japanese woodcuts, whose art styles influenced manga then subsequently, anime. Most of the time, anime is based upon a manga series, but this is not always the case.

There is no doubt that anime offers a window into Japanese culture, in part due to its virtually limitless versatility. Anime ranges from Evangelion, a science fiction mecha series all about human’s post-apocalyptic battle against an alien threat, to Chihayafuru, which follows a school club dedicated to playing karuta, a traditional Japanese New Year’s card game. With anime’s breadth comes its ability to demonstrate different aspects of Japanese culture. Chihayafuru is a perfect example, revealing the importance of a popular game in Japan, as well as giving an example of a subculture. Subcultures are numerous and especially prominent in Japan.

It’s interesting that Chihayafuru presents a subculture, because Japanese anime is itself a subculture. But, as the word implies, subcultures present an ultimately limited view of Japan. Indeed, many in Japan do not watch anime or read manga. In addition, there is no doubt that, just like Hollywood presents an idealized America, anime presents an idealized Japan. As I mentioned, anime is above all, a visual medium. There is a prominent perpetuation within it of Japan as an aesthetic. Often, such as in Shinkai Makoto’s achingly beautiful Your Name, actual locations are drawn in and used for scenes. This has led to an entirely new segment of tourism and a new word to describe it: Seichi junrei, literally, sacred pilgrimage. Anime fans are now flocking to locations all over Japan to see where their favorite anime took place. Mostly, Japan has welcomed these tourists with open arms, and they’ve been pumping much-needed capital into a lagging economy. I worry, however, that cities like Tokyo and Kyoto will go the way of Paris and Prague, sought out more for their aesthetic than their history, culture and people.

The Asian diaspora is contributing to this view of Japan as an aesthetic. A particularly funny example of this came up recently on the Subtle Asian Dating Facebook page. A user put together a collage of the dating profile photos of young Asian men, all standing in the Gates leading to the Fushimi Inari shrine in Kyoto. Photos like these bring to mind the pictures of white Americans standing before the Eiffel Tower or Notre Dame in Paris. These landmarks are aesthetic markers of the city, being now stripped of nearly all their historical and cultural relevance. We go to Notre Dame because we know it is famous. However, we don't know why it’s famous.

If we consume culture without context, we are no better than the Americans in the 1950s gawking in gruesome fascination at Godzilla’s rampage through Tokyo. Japan, as a culture and political entity, has a complicated and often ugly past, and knowledge of this past is essential for the understanding of anything it produces. I would implore members of the Asian diaspora to seek out context, both cultural and historical for any Asian export they consume.