Four Things I Learned From My Japanese Friends

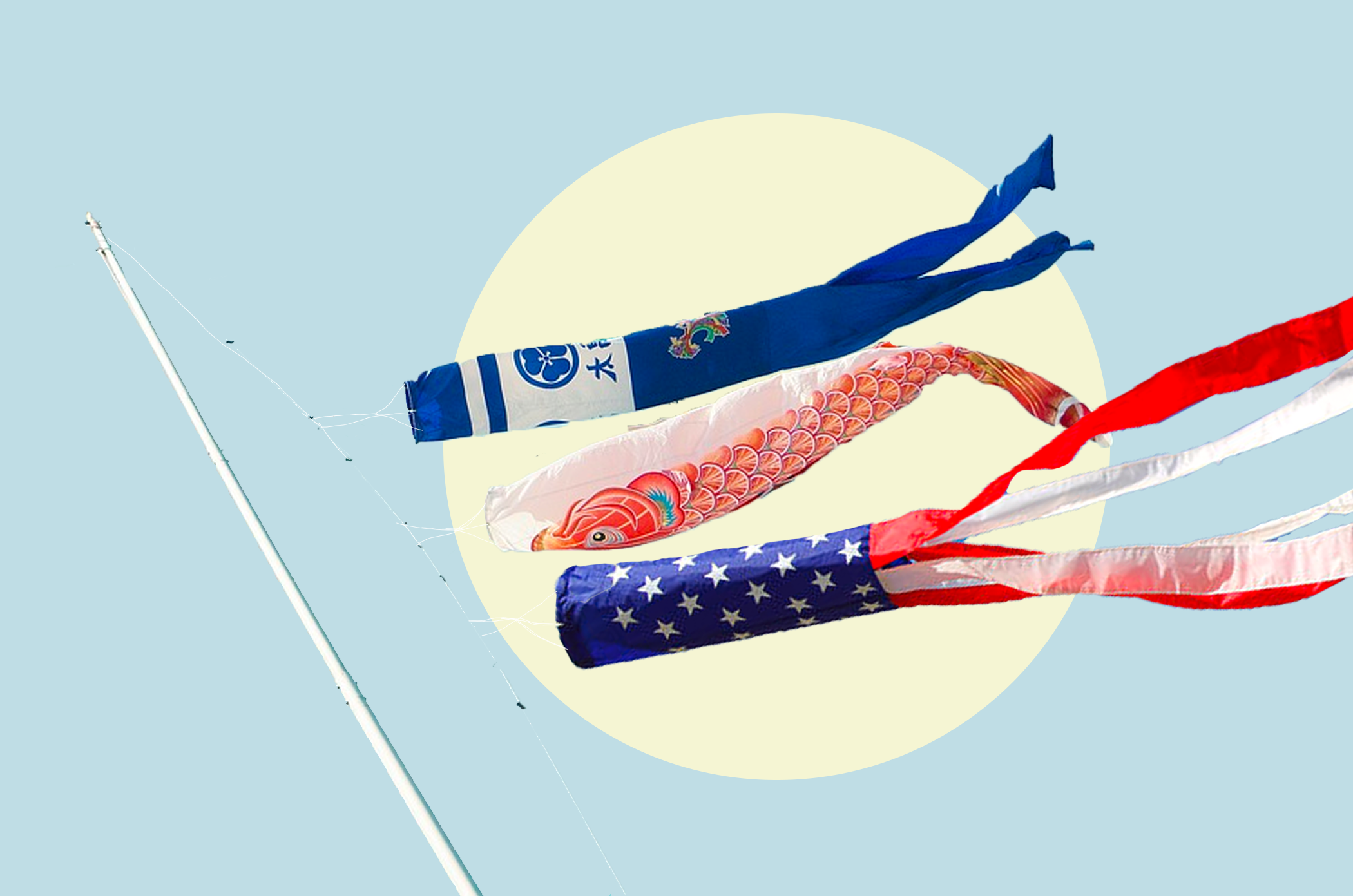

Art by Amy Luo

Studying Japanese language and culture in high school, I consumed all the information that I learned while unconsciously creating a sort of exaggerated version of Japanese society in my head. It naturally happened the same way some of us absorb all the horror stories about adulthood –– the neverending debt, the loss of school friends, the constant stress of jobs –– and fear it until we actually experience it ourselves.

For me, learning about the senpai-kouhai culture (a vertical hierarchy that emphasizes respect for authority) prevalent even in settings like after-school clubs, and being trained to master the “polite” or “honorific” forms of speech in class intimidated me away from the idea of studying or living abroad. The cultural differences seemed too drastic to me. I thought that my habits from my upbringing in the U.S. –– where I could easily interact with classmates who were older and younger than me without too much attention to my speech or behavior –– would label me as a disrespectful stray if I were to live in Japan.

This was the case until I got to participate in Kizuna Across Culture (KAC)’s Global Classmates Summit, a program that brought seven American and seven Japanese students together for a summer. Though the program is usually held in-person at Washington D.C. every year, the past two cohorts (including mine) were limited to synchronous online interactions. Nevertheless, those opportunities to actually interact with the people whose culture I’m learning taught me that our cultural differences were not as large as I thought them to be.

Here are four things I learned from my Japanese friends:

1. Japanese people are not always more shy or quiet than their American counterparts.

On the first day of the Summit, the American and Japanese participants met in two separate groups to allow us to first warm up with those from our own country. I recall one of the program managers, who was in charge of hosting our first meeting, telling us, “I don’t mean this to be stereotypical, but we have noticed in past years that our Japanese participants tend to be more hesitant to lead the discussion, so it would be really helpful to us if you guys can chip in to keep the conversation going if that happens.”

So when we held our first group discussion the next day, I was surprised when before I even got to press the “Raise Hand” button on Zoom, Ayako (KAC’s president) called out, “Go ahead, Ai.”

Ai, a high school senior in Shizuoka, unmuted herself and confidently started sharing what the Japanese participants had discussed with each other the day before. Chihiro, another participant from Kanagawa, had already raised her hand to go next. With imperfect English yet unwavering voices, they started sharing their thoughts.

I sheepishly reached for the “Raise Hand” button when after their turns speaking, Ayako suggested, “Why don’t we have an American participant go next?”

2. You don’t always need to be super polite to Japanese people –– they’re just as friendly and easygoing!

Ai smiled and started, “So we’re speaking in Japanese right?”

The staff, who seemed to notice how the virtual setting took away some opportunities to break the air of formality, proposed to keep our Zoom meetings open while all the staff left after our 3 hours officially ended so that we could actually get to know each other without feeling monitored. That day’s after-session theme happened to be “Japanese language day,” so all of us were challenged to speak only in Japanese.

“Yes, I think so. My Japanese is not very good, so please excuse my mistakes,” I replied in the polite language form as I have been trained to do for the past four years in class. My textbooks had always emphasized the importance of showing respect through speech, teaching that politeness is a widespread societal habit. Knowing this, and the fact that students aren’t exempted from it, I imagined that many interactions with Japanese people would feel stiff, including in our small circle of high schoolers.

Jaylen, one of my fellow American participants from Chicago, piggybacked off the topic to share, “Studying Japanese is really hard because of all the Kanji we need to memorize.”

The Japanese students quickly nodded sympathetically, and Miu replied, “We’ve been living in Japan since we were born, but we struggle with it too.”

I felt a burden lift off my shoulders when I noticed a few of the participants occasionally starting to speak in the casual language form. I guess I don’t need to worry too much about the -desu (polite ending) that I forgot to add at the end of my last sentence.

The stories of mutual hardships in learning another language led to a conversation about interesting hobbies, which then led to a mini talent show where Clara, a senior from Illinois, played the accordion for us, followed by Kota from Hiroshima playing the guitar. The mini talent show was followed by a group chat formulation and us Americans spamming it with memes for our new friends who were less familiar with it. The spam session was then followed by a long exchange of movie recommendations.

I smiled excitedly as I added the movie Perfect World to my watchlist. I think we get along really well.

3. Japanese students aren’t any less willing to go for non-traditional careers than other countries.

“Let’s start our discussion about cultural association. To start off, I’m curious if there was anything that surprised you when you met the other country’s participants. Does anyone have anything to share?” Ayako asked.

Jaylen raised her hand. “I was surprised to see that some of the participants have very non-traditional career aspirations. For example, Ai mentioned that she wants to be a radio personality, while Kota wants to be a film director and Ryo a tour guide. I personally haven’t met anyone in my school who wanted to be any of those yet because they weren’t considered ‘safe’ careers, so I was curious if you ever had that kind of pressure when thinking about life after school.”

I nodded to show that I was curious about the same thing. Being mostly surrounded with fellow immigrants while growing up, many of my friends and I always had some sort of pressure to go for a career that could bring lasting reward and stability to our families, so it was eye-opening to see such a diverse lineup of career aspirations from the Japanese students. Even in non-immigrant American families, there was always an unspoken hierarchy of careers seemingly embedded into people’s minds. Maybe it was Japan’s more conservative image or their reputation as a high-tech society that convinced me that it might be more so the case in Japan.

Ai unmuted herself to reply. “There aren’t a lot of people who want the same career as me, but I personally never felt very discouraged from doing what I want to do. Even if I want to become a radio personality, I’m still working hard to be able to study what I want in the future, so I don’t feel that different from anyone else.”

Kota agreed, “Even if filmmaking is my dream, I prepare as earnestly as anyone else, so I don’t feel treated any less. I also think it’s most important to just do what you want to do.”

“I come from a small town in Ehime where hospitality is a strong value, and we have a lot of pride in our hometown even if we don’t get as many visitors as cities like Tokyo. I think because I have a strong ambition to show the charms of our city to other people, the people around me have been supportive,” Ryo added.

Stunned and impressed, we could only grin. “We would really love to see your shows, movies, and tours someday.”

4. Even if we grew up in different cultures, we still struggle in the same ways and can succeed in the same ways as well.

It was the day of our final presentation. From the very beginning of the summer, we were notified that we would need to collectively deliver a presentation about our ten days together to an expected audience of about 90 to 100 people.

“I’m so nervous,” Miu breathed out.

“Me too. I’ve never given a presentation before,” Chihiro chimed in.

Since there is a more passive education system in Japan, the Japanese students have rarely been given opportunities to present, unlike us in the U.S. where we have been taught to give class presentations since a young age. And whereas we were encouraged to turn on our Zoom cameras and participate during online learning, many Japanese students were required to keep their cameras and microphones off the entire class.

Nevertheless, I was extremely nervous too, and I wanted them to know that they were not the only ones freaking out. “My palms are sweating,” I laughed.

“I think we’re all really nervous,” Clara agreed with a reassuring smile.

“It’s kind of like how you said living in Japan your whole lives doesn’t make learning kanji any less difficult. But we all practiced, so we’re all prepared. We will all do fine, don’t worry,” I put my hands in fists and shook them enthusiastically to encourage them.

Since we grew up in different places, I thought that our individual set of difficulties would be different and hard to understand. For example, I didn’t expect them to understand what it felt like to grow up surrounded by people who didn’t look like me. But they were quick to listen and acknowledge our experiences, while also sharing times they witnessed discrimination in Japan in different forms –– against women, against foreigners, and against the disabled. Knowing that we were not as different as I thought at all made me feel a lot less alone when I faced upcoming challenges like our presentation, and I hoped that they felt the same.

Jaylen taught us an exercise for getting rid of nerves from her experiences in school theater, so we laughed as we physically started jumping around in our bedrooms to shake off the tension in our bodies.

When the presentation started, I felt my heart swell up with pride as I watched everyone present what they have been rehearsing nonstop for the last 48 hours. We all messed up a bit, but we all ended with a happy and relieved smile. After our voices created a sea of “thank you”s and “arigatou gozaimasu”s, I logged off the webinar and opened my phone to a stream of congratulation stickers in our group chat.

With wet palms and still shaking fingers, I joined in.

“We did it! I’m so proud of us.”